The Tangible and Intangible Components of Cultural Heritage

LEED Initiative joins the celebrations for Heritage Treasures Day, commemorating the efforts put into preserving monuments and raising funds for iconic landmarks all over the globe.

The word “heritage” holds the weight of the past, offering an opportunity to shine a spotlight on those who have shown utter strength and resilience during what has been a challenging time. In this light, the realm of cultural heritage does not only venerate physical structures or locations such as historic buildings and archeological sites, but also encompass arts, music, sculptures, books, customs, rituals, ceremonies, and craft. These tangible cultural forms are living expressions passed down over the years from one generation to another. They display the evolution of societies and thus help us examine our histories.

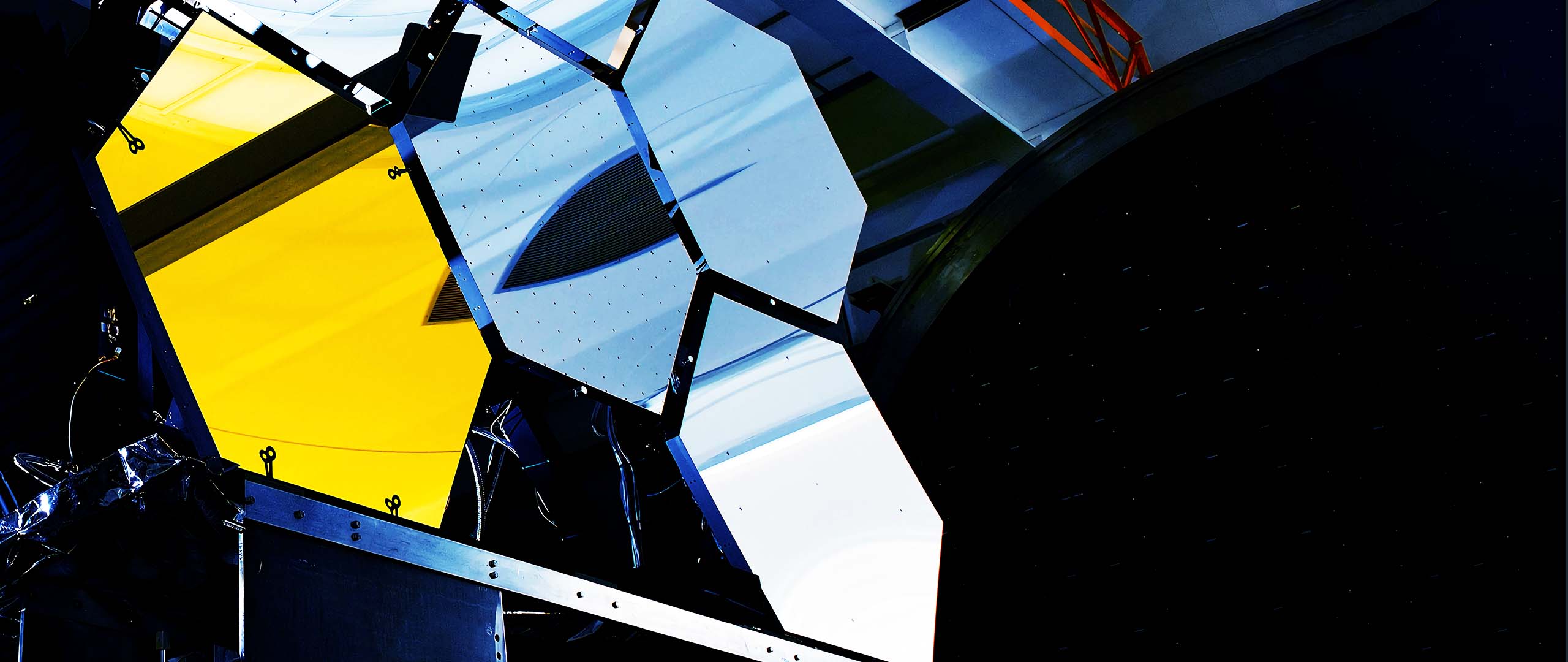

Tunisia has a rich and diverse heritage due to its strategic Mediterranean location. It was the home to a plethora of different civilizations and it is worth mentioning that seven sites and monuments are UNESCO World Heritage: Carthage, Dougga, El Djem, and Kerkouane and the medinas of Tunis, Kairouan and Sousse. As a matter of fact, the Roman Amphitheater El Jem, listed as a World Heritage Site in 1979, is one of the largest coliseums in North Africa, capable of accommodating 35,000 spectators. Embodying the glory of the Roman Empire, this grandiose amphitheater was built in the 3rd century and is located in the governorate of Mahdia.

Preserving these monuments and raising awareness among young people on heritage and cultural diversity is one of the prime goals of national and international institutions operating in Tunisia. In this respect, Mohamed Ali, a young entrepreneur and the founder and executive director of Digital Cultural eXperience wanted to capture the Tunisian collective identity through the lenses of cultural heritage by developing a mobile application. The latter is called “World Heritage Sites in Tunisia” and it features an interactive map, engaging audio guides and 360° pictures to promote the 7 cultural World Heritage in Tunisia in an inclusive and youth-engaging format. His initiative was supported by the UNESCO-UNOCT project on the Prevention of Violent Extremism.

Cultural Heritage as Bacons of Affect and Politics

Moreover, there is an intrinsic correlation between cultural heritage and one’s collective identity and sense of belonging. In this respect, a sense of deep connection to the past and being part of a historical continuum is born. Only through having insights into the past, can we immerse in the realm of cultural engagement and shape our future pathways. It is the fact of knowing where we have come from help us discover where we want to go. This train of thought was the pinnacle of Jon’s Hawkes book The Forth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning, where he contemplates how our social memory and our repositories of insights and understanding are essential to our sense of belonging. He adds that without a sense of our past, we are adrift in an endless present. Hence, this generates a sense of shared ownership and collective identity that spurs us to indulge in cultural activities related to one’s heritage.

There is a growing body of research within Critical Heritage Studies that examines the emotional and affective nature of heritage and memory, more specifically the notion of nostalgia. The latter is classically defined according to Britannica Dictionary as a pleasure and sadness that is caused by remembering something from the past and wishing that you could experience it again. It is an important motivating emotion or affect, a way of being moved by the past. It is through nostalgia and mobilizing emotions that we dwell on the past to carve our present and influence our future. This sentimental value can be seen in the possession of some family heirlooms that may be passed from one generation to another like a ring, a watch or a scarf.

As examined above cultural heritage posses a political power in relation to identity and belonging. It points to the past and generates the material anchors of our narratives and thus our lasting collective identities. As much as cultural heritage is an expression of one’s communal identity, it can be seen as an expression of difference to minority groups or those who do not belong or fit in in the community. Here, we have embroiled in identity-based conflicts and in this case cultural heritage is a threat to one’s identity and sense of belonging. It can be seen as a tool for social control and dissent especially when it involves social minorities navigating their complex interplay of belonging, nationalism, collective memory and security.

In conclusion, defining cultural heritage can be the catalyst of debates revolving around politics, power, identity, and affect. As we are today more aware of this sturdy interplay, what we must do is protect, promote and share a cultural identity. Only then we can foster a culture of acceptance and tolerance.

The article represents the views of its writer and not that of LEED Initiative.