Is It Fair to Have to Fight for the Right to Marry?

Same-sex marriages have been a topic of debate and controversy in India for a long time. While homosexuality was decriminalized in 2018, same-sex marriage remains illegal in the country.

The fight for marriage equality that continues to unfold in India today posits a bigger question regarding the institution of marriage in the subcontinent. The legal backup that marriage can provide for the citizens of India cannot be discounted, despite its legacy being recorded in history as a double-edged sword. The world continues to ponder over non-binary individuals’ fight for marriage equality in India today. This article deems to delve into the matter deeper to analyze the complications that come with the petition submitted to the Supreme Court.

Section 4(c) of the Special Marriage Act of 1954 defines marriage as a union between a ‘man’ and a ‘woman’. Two same-sex couples took to the Supreme Court of India to address this issue in an attempt to instill an amendment. The petitioners point out how the inability to get legally married denies them the privileges of retirement benefits, joint bank accounts, inheritance recognition, adoption, and surrogacy. Their advocacy efforts to amend the “unconstitutional” Act simultaneously challenge similar laws about marriage like the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955 and the Foreign Marriage Act of 1969. The legislative, social, and metaphysical privileges that accompany marriages in India are denied to same-sex couples and non-binary partners.

The Supreme Court Bench, headed by Chief Justice D. Y. Chandrachud has begun supervising the hearing since November 2022. The collective lawsuit has only grown bigger in popularity, support, and negation from then on, with national and international media dissecting the country’s internal conundrums and inconsistencies induced due to diversities. The five-judge panel including Justice Hima Kohli, Justice Ravindra Bhat, Justice S. K. Kaul, and Justice P. S. Narasimha are analyzing numerous cases across the country from more than fifty petitioners.

On the other hand, the political backdrop of the country has been having a tremendous impact on the national sentiments towards the issue. The government of India continues to persist that the advocacy for same-sex marriage is an “urban elitist” agenda that could violate the crux of Indian tradition. The opposition has argued against the petition, even comparing the petition to incestuous relationships! These arguments have been making headlines for all the wrong reasons for the past couple of months.

At this juncture, a fundamental question arises. What does wanting to marry mean in the country? Does it entail conforming to a set of age-old diktats that seldom make sense in the 21st century or is it inclined more towards altering/appropriating the very notion of a traditional marriage into a more inclusive social agreement?

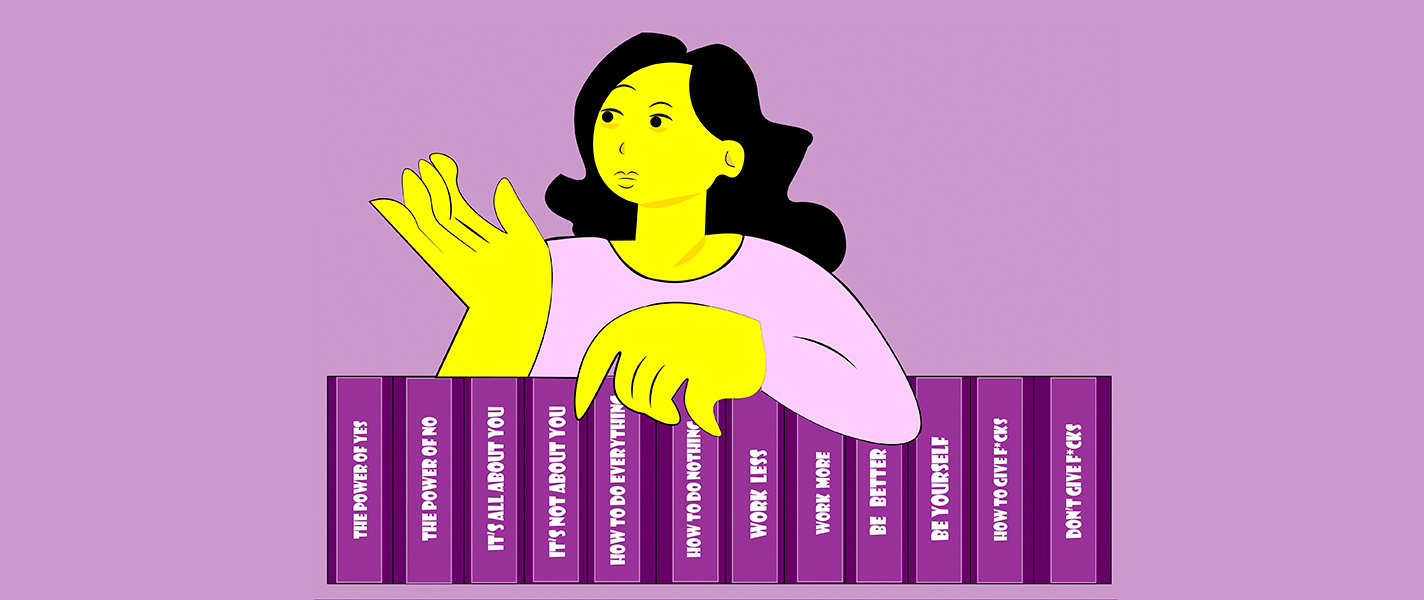

Why Marry When You Can Live Together?

A 2015 study published by the Demography Journal recognized that queer couples get married for more reasons than societal obligations. The study focused on Swedish gay and lesbian couples. It was found that while gay couples preferred to get married for pooling their resources, lesbian couples were keener on joint/step-parent adoption. Hence, marriage might be a very gendered and capitalist institution. Voluntarily embracing marriage could mean giving in to many consumerist notions of celebration and matrimony. However, the right for non-binary individuals to be part of the dominant institution (which may be flawed) is a democratic concern. Appropriating and/or conforming to wedding traditions and rituals are matters of choice. Whether or not one agrees with the institution of traditional marriage, the freedom to exercise it without legal restrictions needs to be availed, according to Article 15 of the Indian Constitution.

Furthermore, it cannot be discounted that the inclusivity enabled by legalizing same-sex matrimonial unions can revolutionize the problematic convulsions of marriage as an institution to a large extent. Call them baby steps, but the transition is evident. Age-old systems of patriarchal hegemony are being compromised for good. The youth of South Asia is waking up to the revolution. In addition to the privileges permitted by a matrimonial union, this move opens up the scope to investigate the loopholes in many existent laws that have been exclusively made to please heteronormativity.

Pensions, Provident Funds, and a Partner

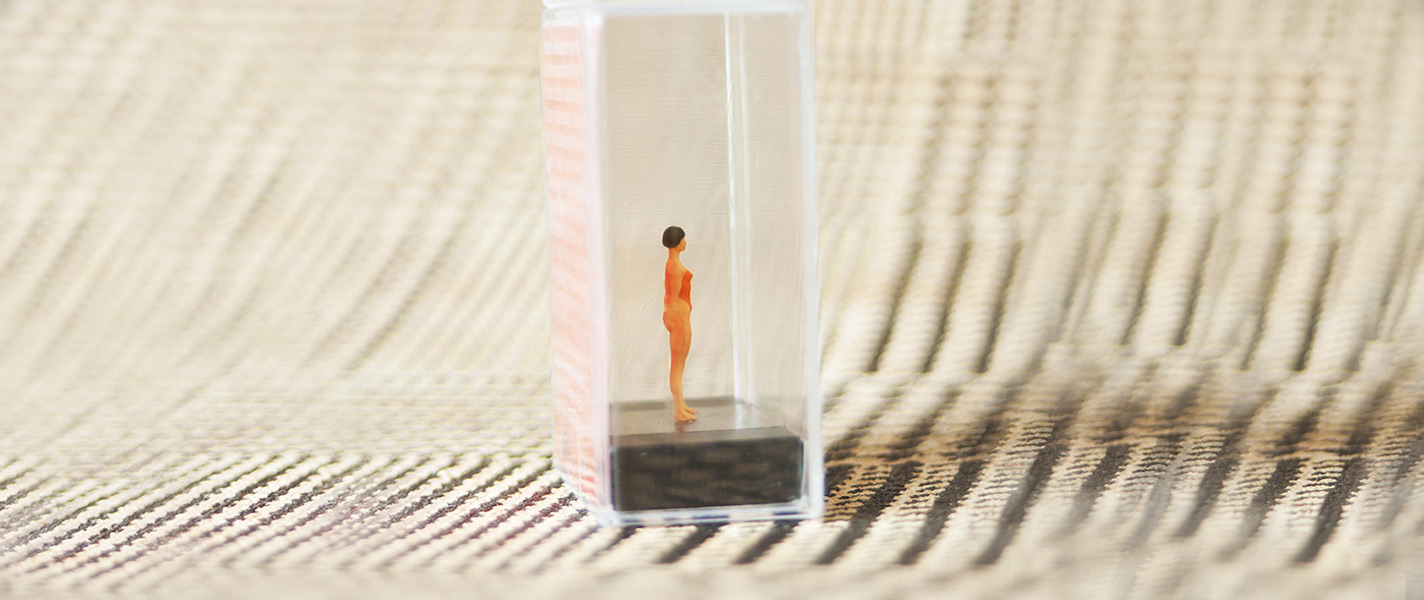

Substituting the conventional idea of a man and wife with that of spouses would seem simple on paper. However, a tiny amendment to the Special Marriage Act does not guarantee queer couples the same treatment as straight couples. Especially in a country as diverse as India, where every marital union is governed by separate religious and legislative rulebooks, the knot only gets tighter. Stepping outside the binary opposition of heteronormativity also poses the challenges of re-drafting many a social notion and law.

The country continues to learn about the huge spectrum of sexualities as each day passes. Every new piece of information presents a fresh conundrum. The minimum age for a woman to get married in India remains 18, while it is recognized to be 21 for men. This discrepancy would treat lesbian unions and gay unions differently, as pointed out by Advocate A. M. Singhvi. Discriminatory laws are the root of concern in the inability to recognize same-sex marriages. According to the opposition’s Advocate S. G. Tushar Mehta, nearly 160 laws would have to be reworked to bring about marriage equality. This shines a light on issues on a larger, more historical canvas.

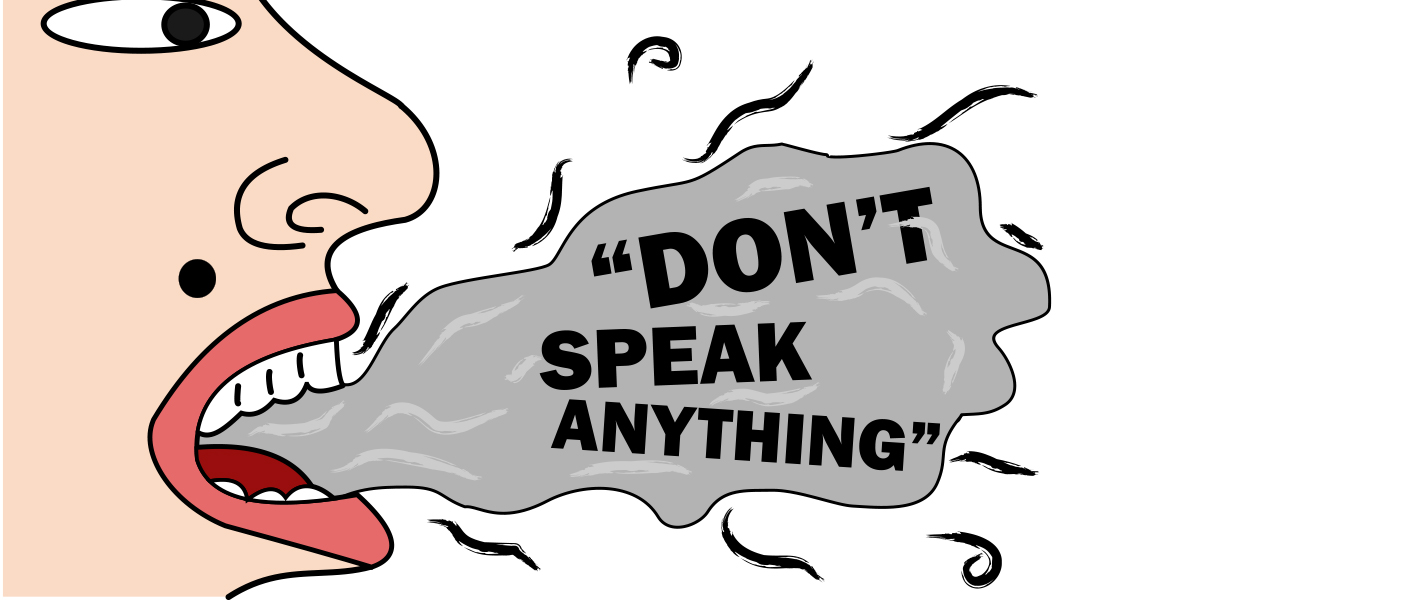

Mehta’s Concerns

Advocate Mehta’s tensions of a future where India’s Supreme Court would have to take up cases seeking the legitimization of incest have been bizarre, to say the least. Although his arguments concerning the possible loopholes of the Special Marriage Act hold ground, his rhetorical questions on who would be regarded as the “wife” in a queer marriage have been absurd. These arguments highlight the phallogocentric complications of our linguistic caliber as well. He continues to scrape for a “compromise” in terms of addressing the queries of same-sex couples without using the term “marriage” in the picture.

Advocate Kapil Sibal was of the opinion that the petitioners’ need is “not a fundamental right, but something short of it, but something meaningful”. The ambiguity surrounding the Act and the future of queer couples in India have also taken a detour to weigh parenthood against (the supposedly superior) motherhood. The debate clearly makes one question the discriminatory hearthstone of India’s legal system.

How Hard Should It Be to Start a Family?

Families are complex, yet important social units that determine a nation’s global stature. India recently overtook China as the most populated country in the world. The decriminalization of homosexuality took as long as 2018 to effectualize here. The impact that the rebuttal of Section 377 had on the Indian political and cultural scene has been humungous. While 2018 served as the first step towards a more inclusive governing system, the advocacy for same-sex marriages calls for a bigger change; one that starts on a fresh page for revisions.

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, the architect of the Indian Constitution, had said early on that his decision to introduce provisions for amendments in it is because he believes no Constitution is for all generations alike. The petition for same-sex marriage vouches for many necessary changes in the Indian social, political, and legislative system. Although it may be a mammoth task to look into these discrepancies individually, it will be worth it in the long run for a country whose biggest asset is its human resource.

The article represents the views of its writer and not that of LEED Initiative.