Democratizing the Internet for the Future

In 2033, 98 percent of the global population will have regular and quality access to the Internet. Being offline is no longer a circumstance but a personal choice.

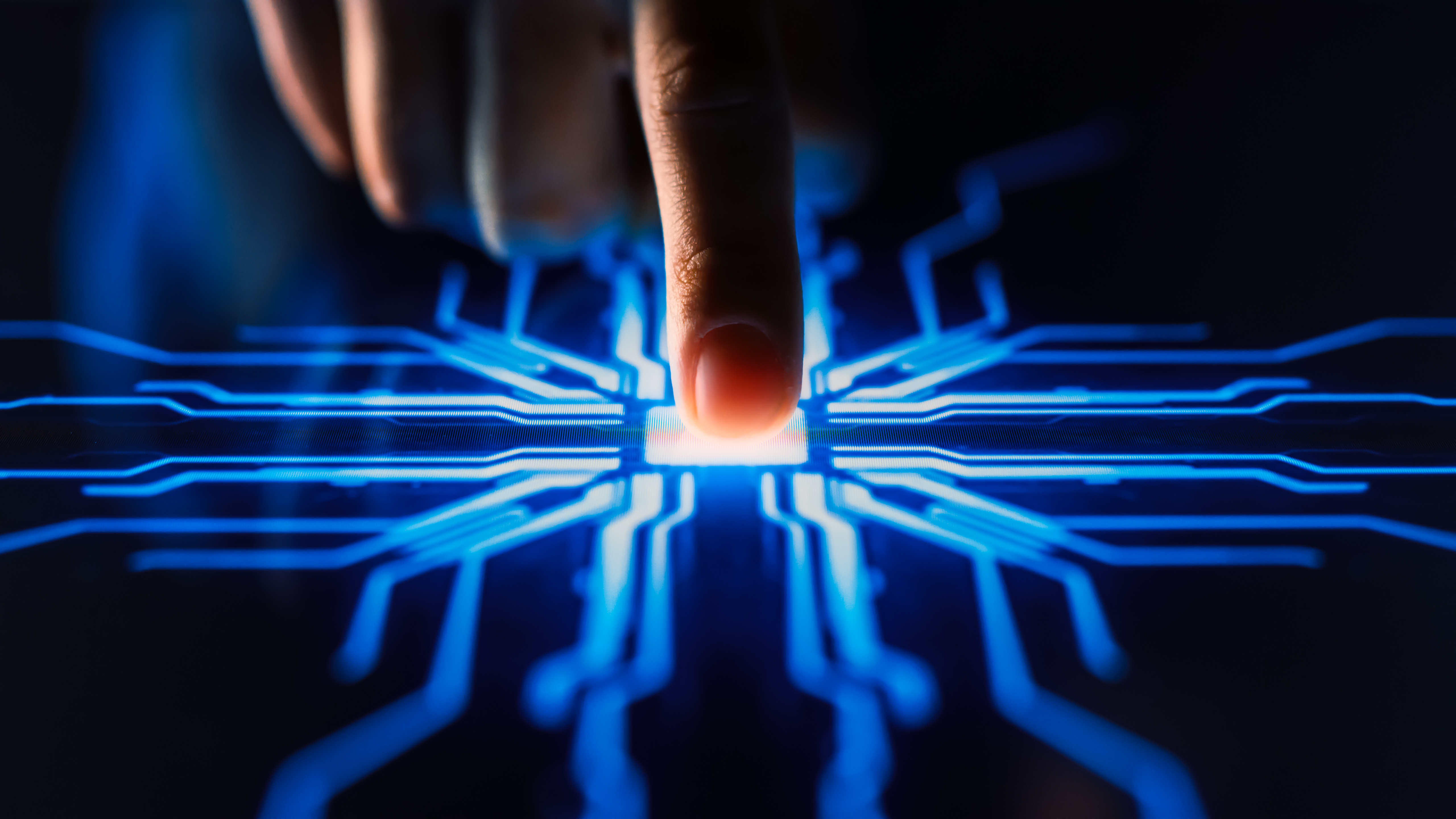

This opinion piece is influenced by a future thinking course offered by the Institute for the Future in Coursera inspired by the present trends in technology. Recently, global artificial intelligence race headlines have been making noise worldwide, presaged with the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT. Tech companies in Silicon Valley are now pursuing pouring billions of resources into a new infrastructure layer of the global economy, predicted to add a boost of USD 15 trillion by 2030. This is just the beginning.

Understanding trends in tech is not easy and often marred with terminologies and jargon: generative AI, blockchains, cryptocurrencies, quantum computations, singularity, and transhumanism, seems like a whole new world. What captivates me is the exercise of imagining future innovations by forecasting present signals. For example, a prospective restaurant that will link generative AI to a 3D food printing machine; if you do not know what to eat, just enter general prompts and decide from AI-generated suggestions. Minutes later, you already have your personally-customized order, or you can have it delivered to your house by drones.

However, I realized that this exercise, exciting as it seems, is a privilege. After all, we cannot blame anyone for not thinking about the future when they are immersed in the problems of the present; where to get the next meal, how to pay this month’s rent, and how to survive, among other concerns. More so, making forecasts and scenarios of the future require updated awareness of present signals and drivers of change. Parenthetically, as the economy shifts toward mechanization and automation, technological disruption becomes a norm; a futures-ready competence requiring the flexibility of constant upskilling and reskilling best undertaken through online learning platforms, as society tends to shift away from a formal-institutional mode of knowledge production. Simplistically said, thriving in the future necessitates a commodity that we can consider today as a privilege – internet access and literacy.

The Diverse Facets of the Concept of the Internet

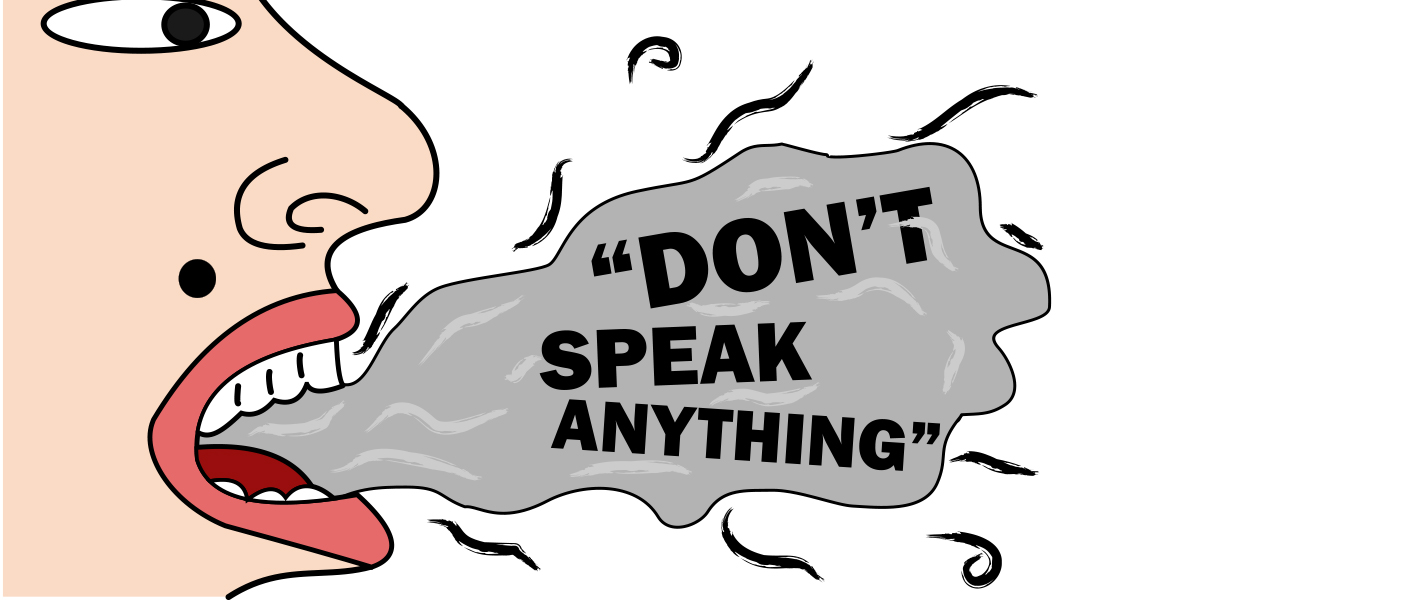

Last 2016, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) passed a non-binding resolution declaring “the promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet”, a provision added under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Although this news created global traction, it remains understated that the resolution focuses on stopping governments from taking away access rather than pronouncing an obligation of states to provide universal internet access to its citizens.

The concept of the internet as a human right does not resonate well with many. Critics argue that the many human rights issues we face appear counterintuitive and impractical to elevate the internet on the same standing as our fundamental rights, such as the right to a dignified life, property, and freedoms. There are also nuanced interpretations that argue that the declaration had not proscribed the internet as a right on its own accord but rather as a means to exercise our right towards freedom and expression, thus the said emphasis on averting takes away access.

On the other hand, let us set an understanding that rights are not competing; rather, they are holistic and interconnected. The lessons gained from the COVID-19 pandemic should impel us to rethink and reflect on the urgent necessity of universal internet accessibility.

First, the internet upholds the right to education as schools were closed due to lockdowns through a transition in both online and blended learning. Second, it was critical to people’s health and safety through the dissemination of COVID-19 information to the public to prevent panic. More so, the global race towards the making of vaccines was facilitated by the internet through connecting the research of the global scientific community in real-time. Third, online discourses became a critical tool in demanding government accountability in their COVID-19 response. It also enabled social movements, initiatives, and volunteerism during the pandemic which are essential tenets of a vibrant democracy. Fourth, the internet greatly helped in cushioning adverse economic impacts by shifting many economic activities online. As an example, the pandemic saw a boom in the gig economy in the Philippines. Fifth, it is a crucial support to mental health by connecting people with each other and providing entertainment during long periods of isolation. Finally, access to local governments through different social media platforms was crucial in seeking help during medical emergencies. In these cases, the internet not only enabled other rights but also literally spelled the difference between life and death.

Beyond counting major impacts, the internet to me, as a first-generation college graduate represents a corpus of knowledge and opportunities; an equalizer from the vicious cycles of intergenerational disadvantage. However, digital inequality is our harrowing present reality wherein billions do not have internet access, and billions more have problems with the cost, ease, frequency, and quality of access. As the world is rapidly changing as we have created a virtual space apart from our physical boundaries – e-governance, e-commerce, e-sports, e-money, ebooks, virtual dating, and online communities, among a plethora of platforms and opportunities – it now becomes a paramount duty of governments to ensure that their citizens will share the benefits of both present and future digital transformations. The key to this is the rights-based democratization of the internet.

Closing the internet gap and achieving universal accessibility in a decade is not impossible with concerted global efforts, especially with push-through citizen demand. After all, a central tenet of future thinking avers that “there are no facts in the future” denoting that the future is not yet decided – it is ours to build. However, the same tenet also tells a cautionary tale; if we do not participate in making the future, it will be decided by others for us.

The article represents the views of its writer and not that of LEED Initiative.