Overcoming the Shadow Pandemic: How a feminist approach to global health policy serves to reduce gender-based violence

We are approaching November 25, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. This day also marks the beginning of the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence, ending with the International Human Rights Day on December 10. This year’s UNITE campaign aims to highlight the relevance of adequate financing as a tool to prevent violence in the first place with the campaign theme “Invest to Prevent Violence Against Women & Girls”.

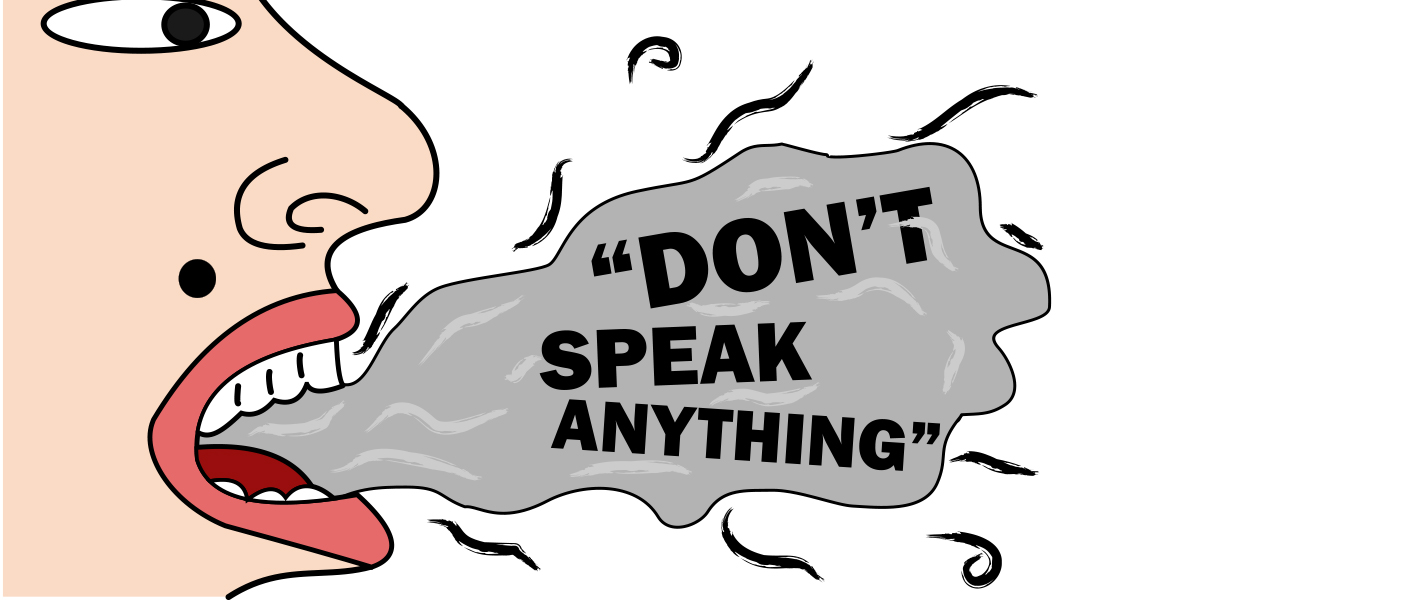

You might feel frustrated, saddened, and paralyzed by what is going on in the world right now and you don’t want to hear any more negative stories. You may also think that current conflicts are overshadowing other global concerns, and you wonder if we really need a dedicated day and campaign every year to highlight gender-based violence (GBV). It is completely understandable if you need a break from bad news. However, gender-based violence will not be eliminated if we do not talk about it. Raising awareness about violence is a crucial first step towards ending it. Moreover, this text is not merely negative but is rather intended to be a source of solidarity, empowerment, and hope for the future.

Gender-based violence: a global threat

First of all, precisely because of the recent severe increase in armed conflicts, it is more important than ever to talk about GBV. Violence against women and children evidently increases in conflict and crisis settings, highlighted for example by research on armed conflicts, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the climate crisis.

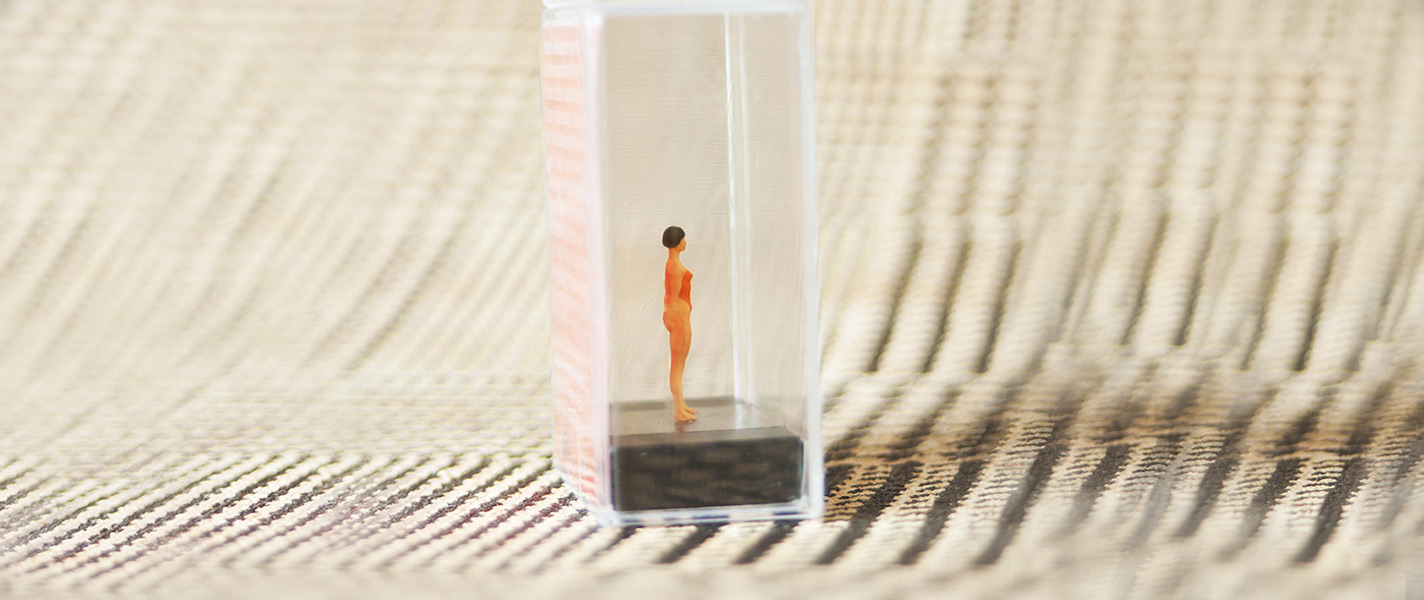

Violence against women and girls (VAWG) is the most common form of GBV, severely inflicting the lives of millions of women and girls worldwide. While it is crucial to name and call out these misogynistic acts of violence, I will refer to the term GBV throughout the text to indicate that all genders are affected and that non-binary, transgender, and gender-diverse people are particularly at risk. Intersecting forms of discrimination lead to individual exposure to violence. Racism, classism, ableism, and other additional forms of discrimination exacerbate the risks and impacts of violence. Humans are not homogenous and should be recognized in their diversity through an intersectional lens. While we tend to first associate the term “violence” with physical violence, GBV refers to all facets of violence including psychological, sexual, online, and economic violence.

GBV and its consequences result from a manifestation of gender inequality and represent a major health threat. In addition to the direct consequences on health, well-being, and quality of life, it severely limits the fulfillment of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and social justice.

In Germany, the country I live in, 133 women were killed by a (ex)partner in 2022. This means that every three days a woman is killed and almost every day an intimate partner attempts to kill a woman in Germany. These are official figures from the police statistics, indicating that the true scale is much greater. Femicides are the most extreme form of GBV. Worldwide, 45,000 women and girls were killed by intimate partners or other family members in 2021. Estimates by UN Women show that globally, 30 % of women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence, leading to detrimental health effects. Considering that more than half of the survivors of violence do not seek help, the health risks are paramount. The figures by UN Women do not include sexual harassment. However, microaggressions, such as verbal harassment and catcalling, also negatively affect (mental) health and well-being. Again, it is important to consider intersectionality and to emphasize the adverse consequences and increased risk of violent experiences for people faced with multiple forms of discrimination.

I have promised that this text will not be all negative. Therefore, I want to invite you to open our imagination space and envision a future without GBV. What would it take to achieve this? Let me present to you the idea of a feminist global health policy (FGHP) as a possible alternative that aims to eliminate GBV.

It’s about power: taking an intersectional feminist approach to end GBV

I advocate for a FGHP, targeted at the political level because we need a system transformation. The occurrence of violence is not inevitable, it can and must be eliminated. It is part of political accountability to adequately encounter GBV. Violence does not arise in a vacuum but is shaped by structures and the distribution of power. This does in no way relieve the individual responsibility of the perpetrators. But in order to end violence, the problem must be tackled at the root.

Feminist approaches to policy aim to end all forms of discrimination. Therefore, they are based on the critical analysis of harmful power hierarchies to ultimately change them. For this to be effective, an intersectional understanding is essential to avoid policies that only serve certain (privileged) populations. By focusing on the most marginalized first, an FGHP intends to be beneficial for everyone, respecting the notion of “Leave no one behind”. An FGHP is grounded in the core values of human rights, equality, decoloniality, and democracy. An intersectional decolonial understanding paves the way for a transformative process that enables health for all and a world free from violence.

However, no policy will be meaningful if it neglects local circumstances. A feminist global health policy must always be developed through a bottom-up approach, embedded in the communities. At the global level only the overarching frame can be established, including the commitment to an intersectional, human rights-based, transformative approach and the importance of reflecting on power. Grassroots civil society organizations and people with lived experiences are the most important actors who can bring an FGHP to life and implement it at the local level. This implies that they must be included in political decision-making processes. The political and legal framework is integral to anchoring an FGHP and ensuring commitment, while meaningful implementation depends on community members. Changing social norms and power regimes can never be dictated, but must emerge through a process of trust and understanding. This is particularly relevant when it comes to violence and its structural causes. While it is essential to have adequate policies and laws, the objective should be to prevent violence in the first place – something only community-led interventions and campaigns can accomplish.

No change without money

Such a transformative endeavor requires resources. Funding is essential for any realizable undertaking since in our capitalist world money is intertwined with power and highly influences decision-making. For good reason, the slogan of this year’s UNITE campaign is “Invest to Prevent Violence Against Women & Girls”. Feminist funding mechanisms based on equity and justice considerations play an important role in eliminating discrimination. By taking into account intersectionality and power in funding decisions, the feminist economy bears a huge potential. In particular, in global health, a field that is highly influenced by capitalist and neoliberal aspirations, feminist funding would bring enormous benefits to the people by prioritizing health advantages over profit-making.

United against violence

Reflecting the spirit of feminist movements, an FGHP thrives on collaboration, solidarity, and empowerment. Just as GBV is a global threat, manifested in patriarchal structures that exist around the world, an FGHP can foster a global movement that unites people worldwide to counter violence, as is already happening by the global campaigns for the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women and the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence. Ending with International Human Rights Day on December 10th, the importance of universal values to advance equality is highlighted. However, as mentioned before, the specific approaches to implementing an FGHP evolve from the community in reflecting the specific needs and circumstances. While we should focus on what unites us and agree on universal principles like freedom from violence, the concrete implementation must always be contextualized.

A global approach that builds on transnational solidarity and unites people in the fight against patriarchy and other oppressing power systems will unleash unprecedented strength. So let’s not lose sight and turn towards the existing spaces of collaboration and empowerment. By collectively pushing for feminist approaches to ending gender-based violence, we may one day make this utopia a reality.

The article represents the views of the blogger and not those of LEED Initiative.